This course is not intended to be a "how-to" of illumination or a history course (per se). The objective is to present a survey of illuminations that span the eras

(if not geography) of history that are covered by the SCA. All of the illuminations presented here come from the British Isles specifically from Durham and Northumbria.

However, there is distinct overlap with continental illumination, and sources for such material will be discussed.

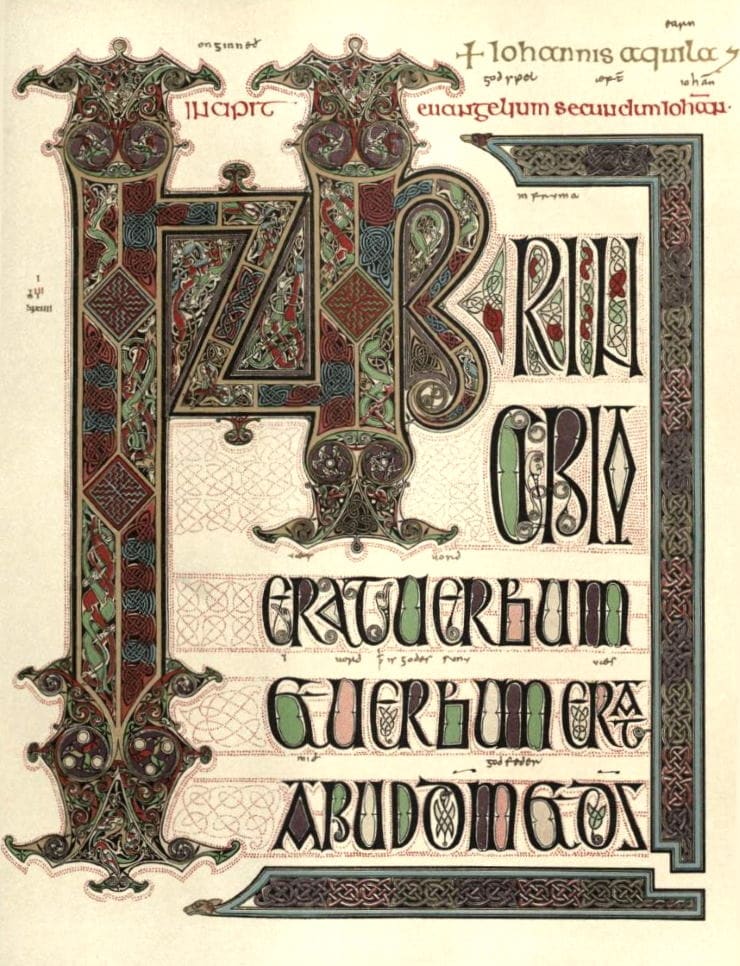

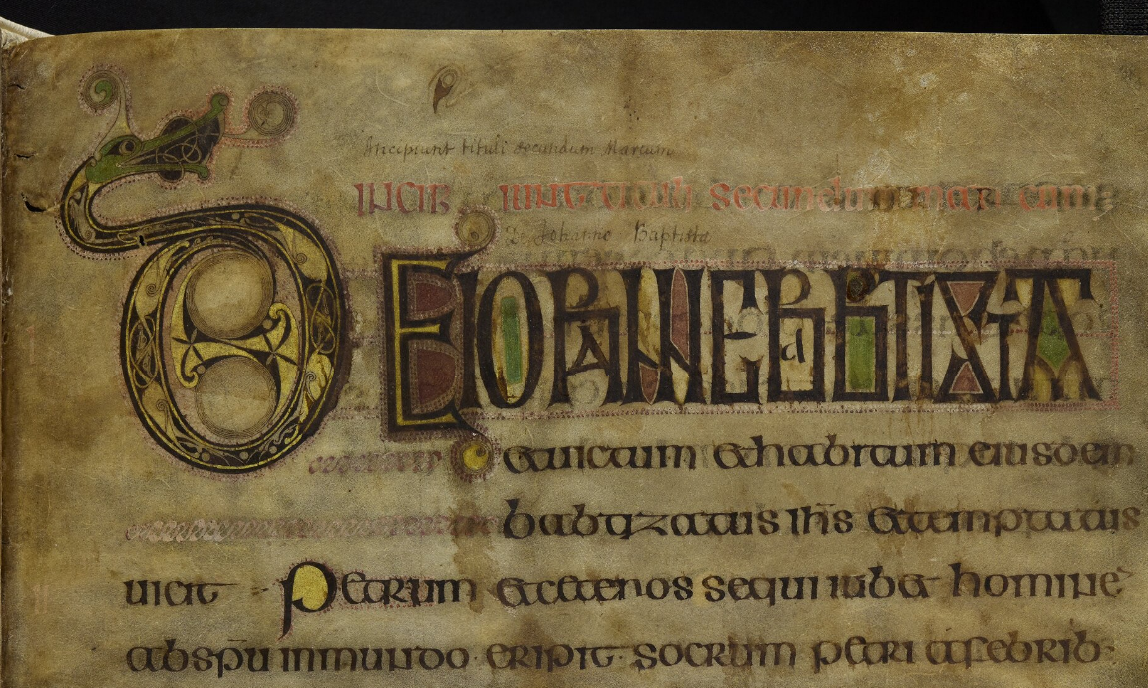

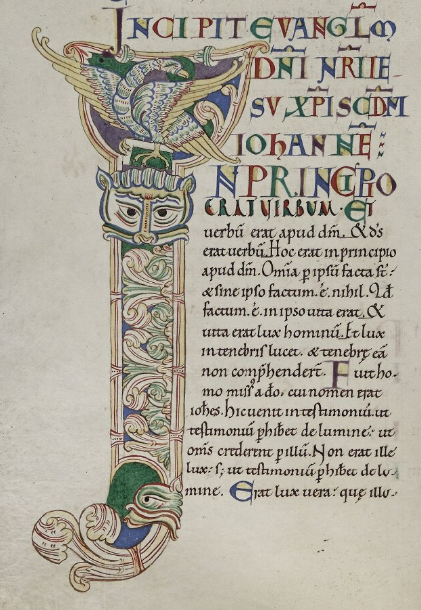

A page from the Lindesfarne Gospels : Gospel of St. John

The Lindesfarne Gospels are one of the earliest surviving examples of book painting.

The manuscript was produced at the monastery of Lindesfarne (on the Northumbrian island

of Farne) towards the end of the 7th century. The creation of this manuscript was in

honor of St. Cuthbert. This page shows some of the hallmarks of Celtic illumination:

the series of red dots that follow the contours of letters and then, almost playfully,

form other patterns. The earliest examples of illuminated letters were simply colored,

and as the art of illumination matured, the letters themselves were decorated with knotwork.

In contrast to the Lindesfarne Gospels, the Book of Durrow has completely abstract designs

in which knotwork completely fills the interior of letters and spiral patterns unfurl at

every terminal.

|

|

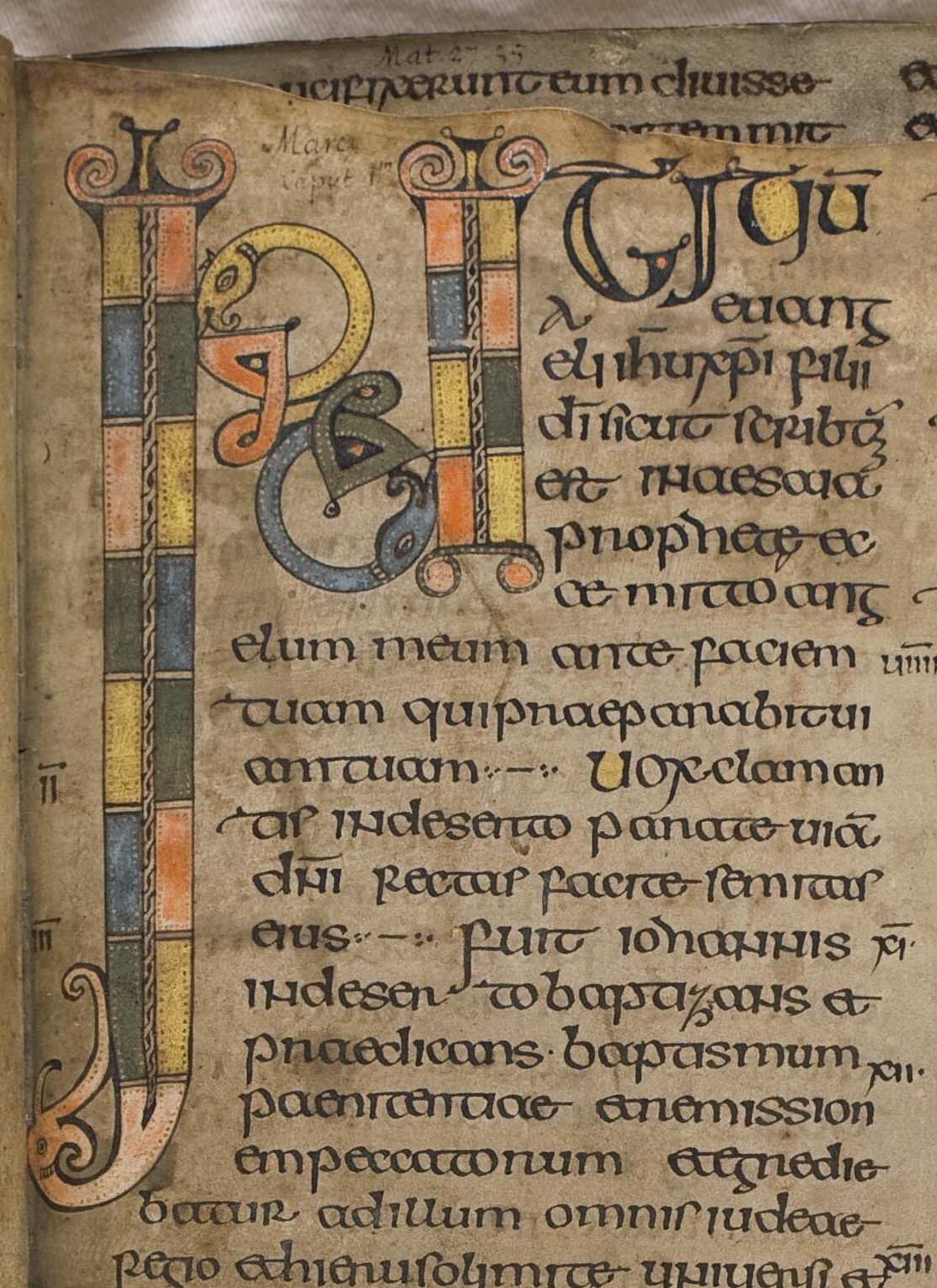

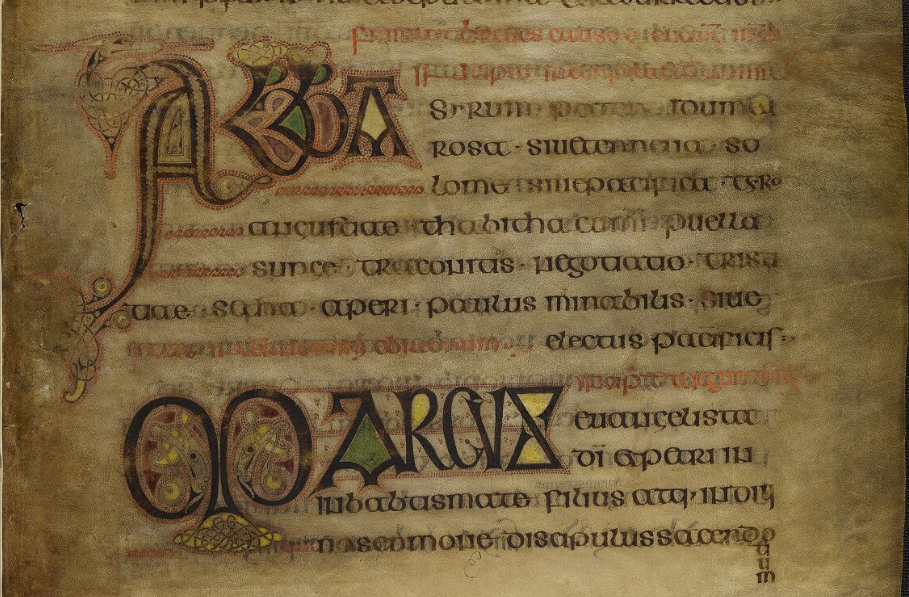

Initial from the beginning of the Gospel of St. Mark

This is from an unidentified manuscript from the 7th century. Of interest here are the zoomorphic fish and the simple running "laces" that follow each side of the letter.

It is somewhat unsophisticated compared with the Lindesfarne Gospels, but it has a simple beauty all its own. Scribes may wish to take note of the leading serifs

of letters and what we would consider unusual puctuation.

Durham Cathedral Library, Manuscript A.II.10. is a fragmentary seventh-century Insular Gospel Book, produced in Lindisfarne c. 650.

|

|

Illumination from the Durham Gospels.

The Durham Gospels date to somewhere between the 7th and 8th century. This particular illumination display simple knotwork flourishes and only three colors!

Durham Gospels, Durham United Kingdom, Durham Cathedral Library, MS A.II.17 Cambridge, Magdalene College Library, MS Pepys 2981, no. 19

|

|

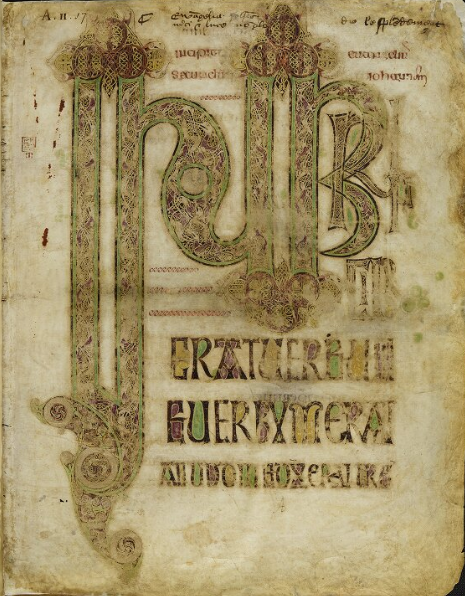

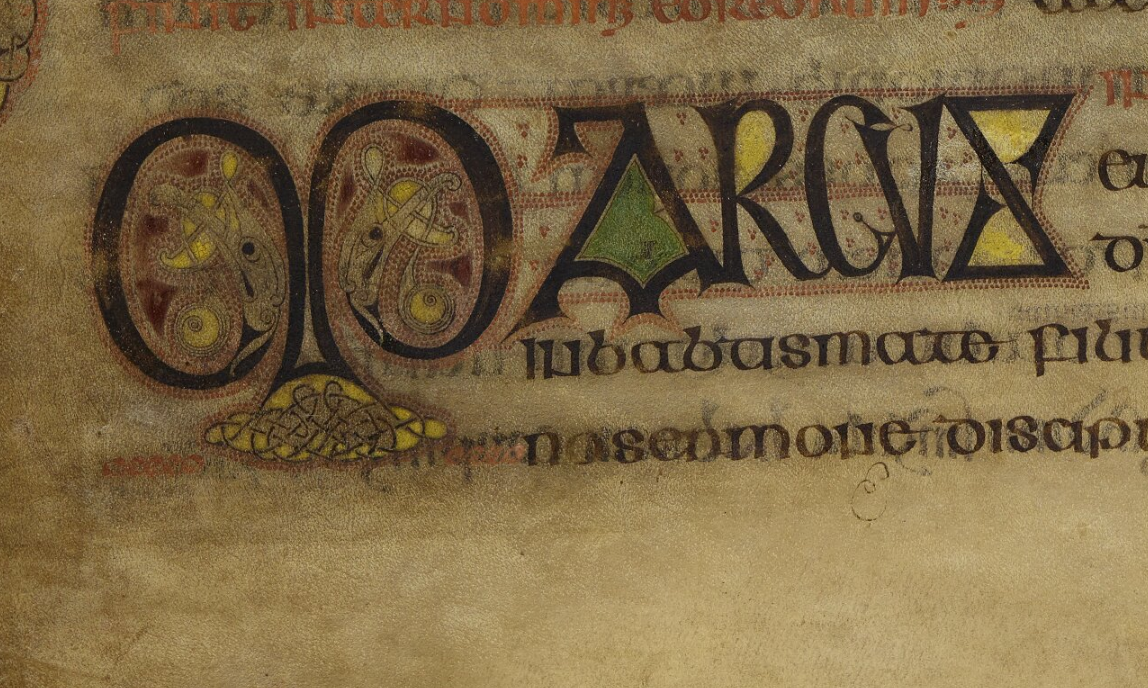

Gospel of St. John, from the Durham Gospels

This is a different example of Celtic knotwork. Note the triskele patterns. The text

is definitely subordinate to the illuminations. If you look closely, you will find

zoomorphs inside the knotwork of the illuminated letters! A good point to bring up is that

in an age of illiteracy, the written word often had a mystical or awe-inspiriing quality.

Illuminations simply enhanced that feeling.

Durham Gospels, Durham United Kingdom, Durham Cathedral Library, MS A.II.17 Cambridge, Magdalene College Library, MS Pepys 2981, no. 19

|

|

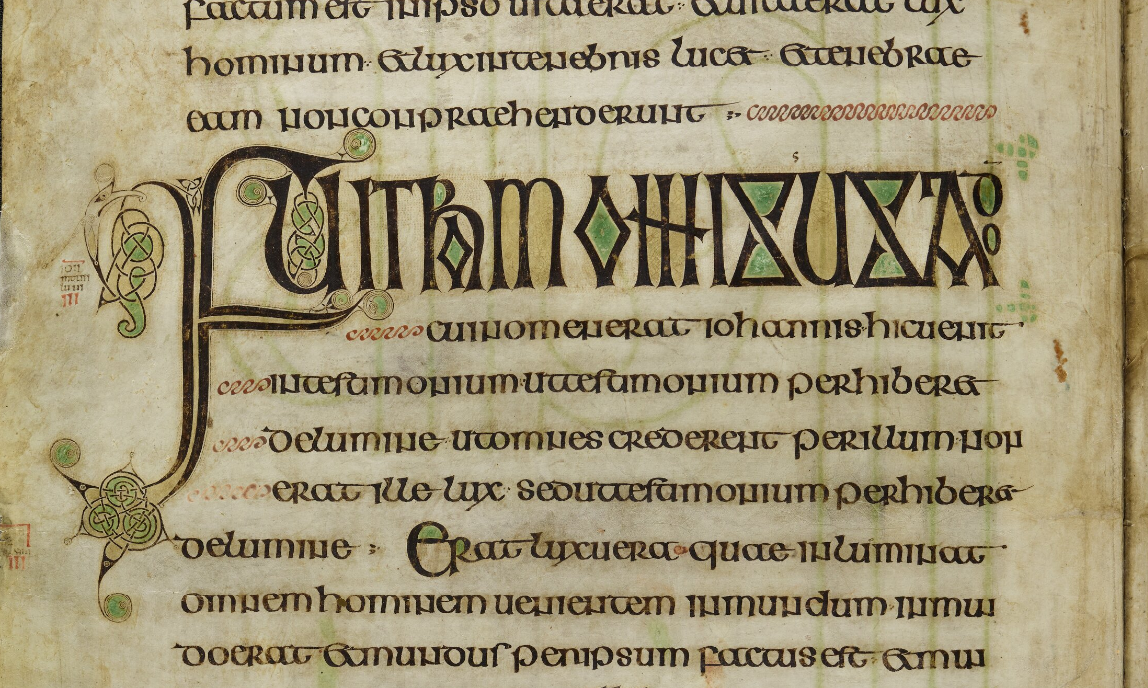

Detail from Gospel of St. John, from the Durham Gospels

A detailed examination of the page shows truly intricate patterns placed in the illumination. We also see that the color used to paint in

some of the zoomorphs appears to be a rich purple. It is worth noting that the "depth" of the illumination is provided by several layers of

rubrication (the tiny dots) that gove the impression of a shadow.

|

|

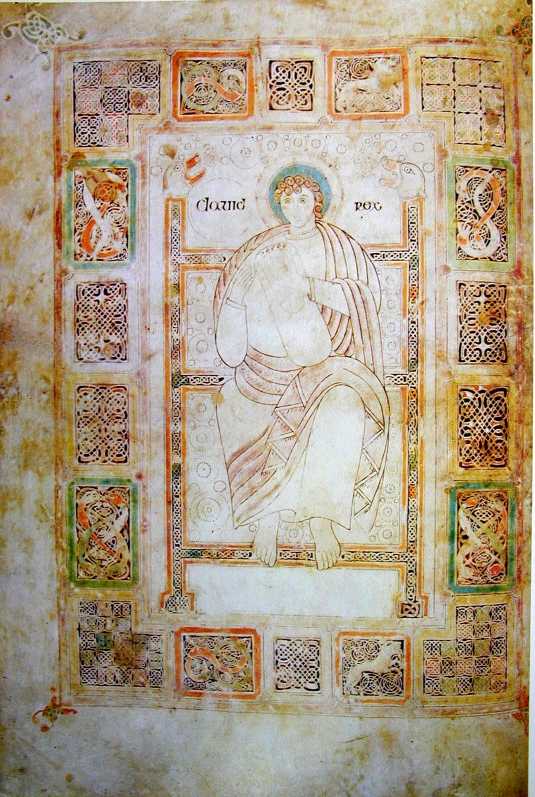

Illuminated "D" from the Durham Gospels

Presumably this is a dragon. Note the mini-zoomorphs inside the letter. Although

loosely termed "Celtic," this type of decoration can be found in Saxon carvings from

the period as exemplified by the door at Kilpeck. it is interesting to note that even single words from a text are also illuminated.

Presumably this is a dragon. Note the mini-zoomorphs inside the letter. Although

loosely termed "Celtic," this type of decoration can be found in Saxon carvings from

the period as exemplified by the door at Kilpeck. it is interesting to note that even single words from a text are also illuminated.

Durham Gospels, folio 38 r4

|

|

Durham Gospels

Note how the letters are interlinked. This page also demonstrates how single letters or even parts of words are accentuated.

Durham Gospels, folio 39 r

|

|

Durham Gospels - detail of MARCUS

Durham Gospels, folio 39 r

|

|

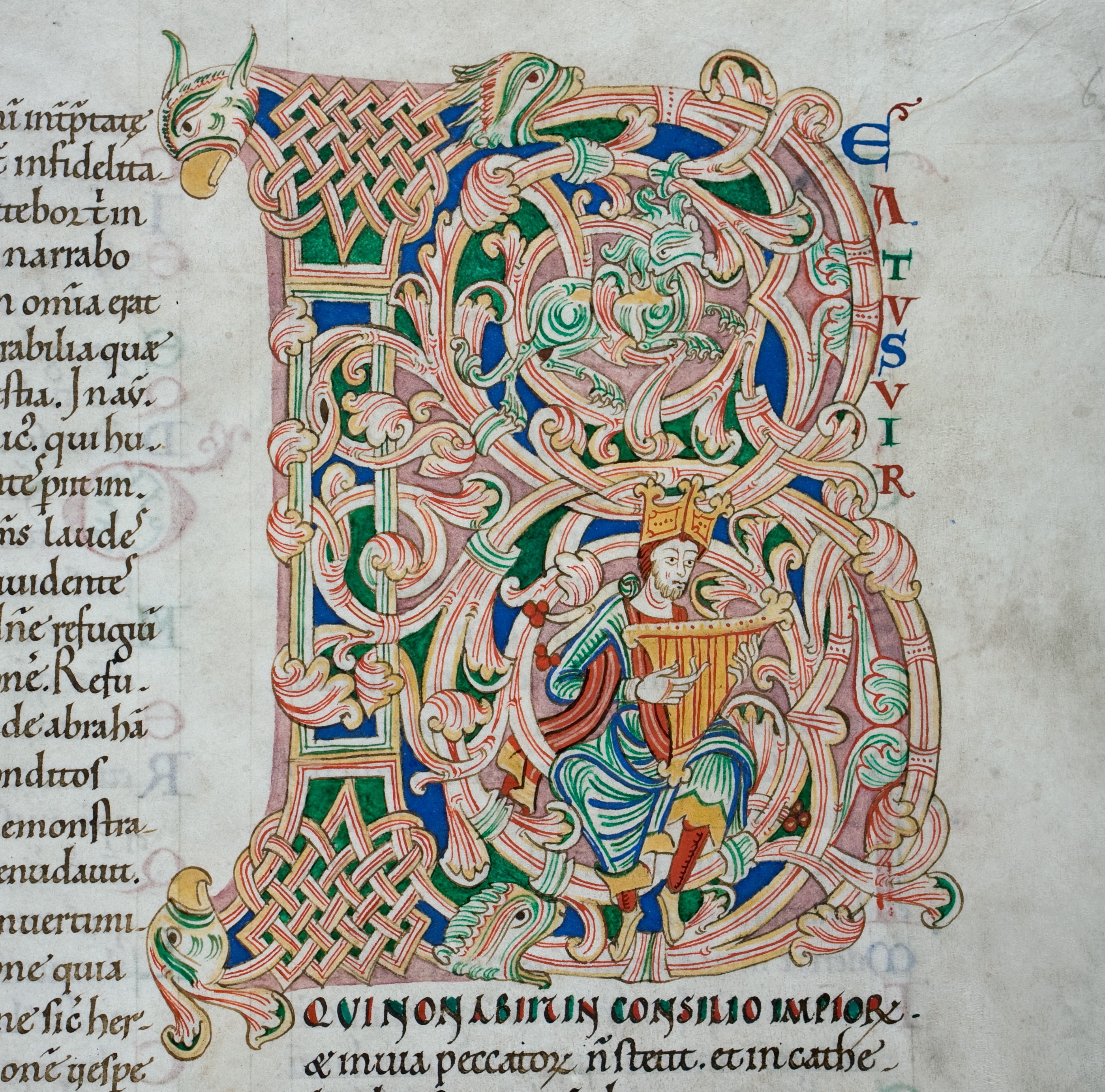

Cassiodorus on Psalms. An 8th century manuscript

This is a relatively simple illumination of King David as a harpist. This depiction closely corresponds to Anglo-Saxon carvings from this period. Note the similarity to the

carvings of Mary (Deerhurst Monastery) and the carvings preserved at Daglingworth.

This is a relatively simple illumination of King David as a harpist. This depiction closely corresponds to Anglo-Saxon carvings from this period. Note the similarity to the

carvings of Mary (Deerhurst Monastery) and the carvings preserved at Daglingworth.

Note that the halo around David's head is a bright blue and the robes hint at a kingly purple.

For those interested in period music or instruments, this illumination can provide the basis for a crude harp or lyre.

|

|

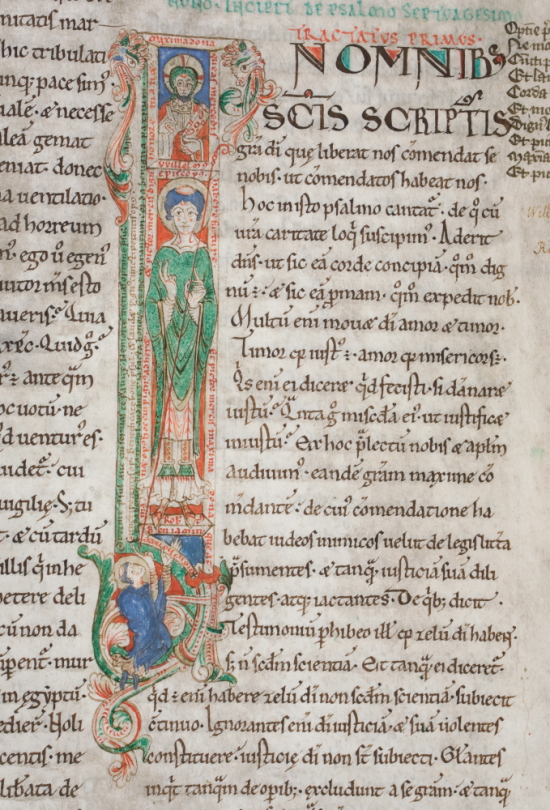

Illumination of Bishop William and Robert Benjamin

This illumination is from an 11th century Bible. If you are confused who these two

gentlemen are, the Bishop is William de St. Calais (1081-96) who is considered the

founder of Durham Cathedral. In addition, William was a "Prince Bishop", meaning he

was expected to wield both religious and military power, and exercise many of the King's

powers--a unique position for a baron in England at that time. In a nice piece of

synchronicity that links back to the Lindesfarne Gospels, the uncorruptable body of St.

Cuthbert is currently enshrined in the Cathedral (his body was taken from Farne Island

in c.897 and brought to where Durham stands now in 995). Also, the Venerable Bede (d.735

at Jarrow) is also buried in the Cathedral (c.1022, after theft by sacrist Aelfred).

Unfortunately, the significance of Robert Benjamin escapes me. Presumably he is the monk who

created this illumination. This is a relatively plain illumination. It appears to be a

simple ink drawing rather than a painted illumination. The evidence of Celtic influence

has faded, and the Saxon like beastheads are more prominent.

To understand the Norman influence we see here, it is work taking a look at examples of

French illumination from the 10th century (Zaczek, p.72). There is a definite Celtic

influence there (Celts were not limited to the British Isles, you know!), but the

treatment of terminals is extremely floral in nature rather than the more primitive-looking

zoomorphs. This floral motif is much more prevalent in continental illumination than in

the British Isles.

Durham Cathedral Library, MS B ii 13, 102r

|

|

An illuminated "D" from the St. Calais Bible

This Bible was created for Bishop William de St Calais during the late 11th century. It is the

earliest illuminated Romanesque Bible with an English provenance. The knotwork has been replaced with a combination of Norman-influenced

arabesques and Saxon beastheads.

This Bible was created for Bishop William de St Calais during the late 11th century. It is the

earliest illuminated Romanesque Bible with an English provenance. The knotwork has been replaced with a combination of Norman-influenced

arabesques and Saxon beastheads.

For example, the rightmost beasthead can be found in the Saxon carvings of this period, e.g. the chancel of Kilpeck.

|

|

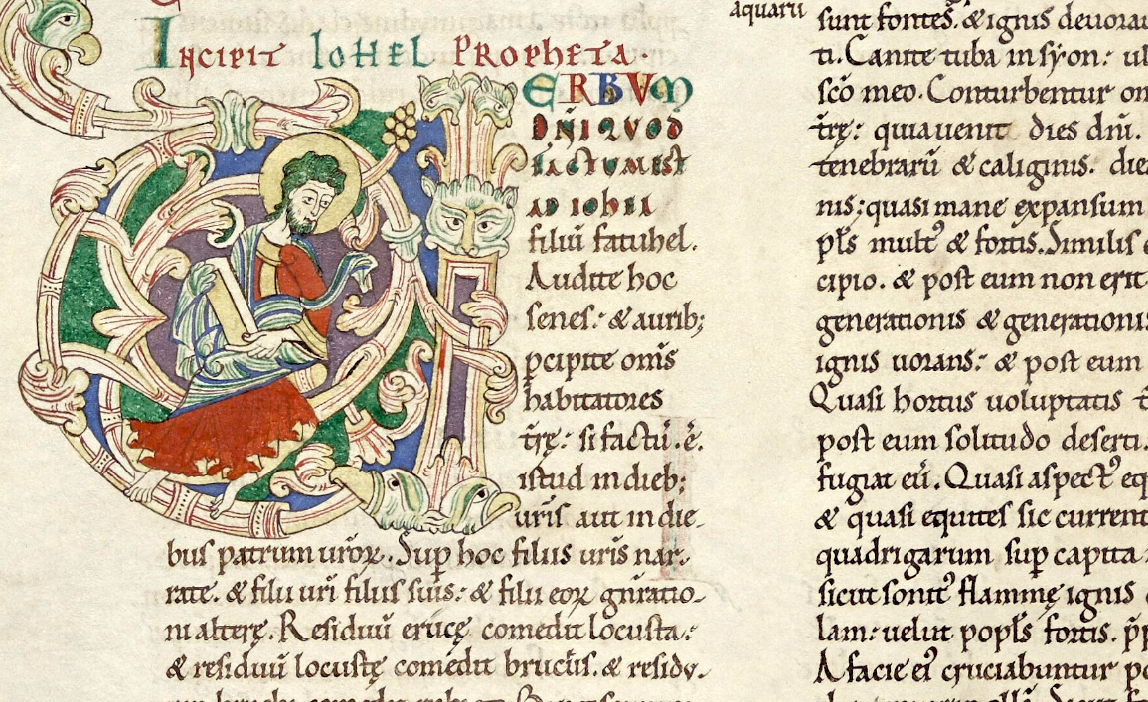

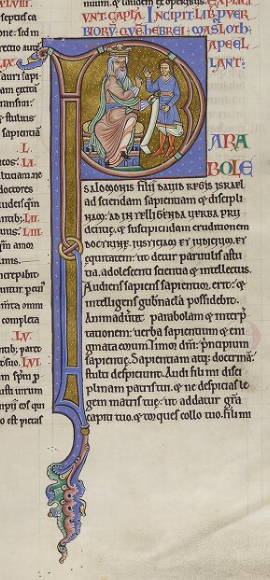

An illuminated "B" from the St. Calais Bible

Some celtic influence remains in the knotwork, but we are still seeing the arabesques. Note the unusual beast in the upper loop of the B.

Letters are emphasized by a simple change in color. Musicians will notice that the harp now reflects a shape more reminiscent of what

we consider to be a modern harp versus the lyre shown in the Cassiodorus.

|

|

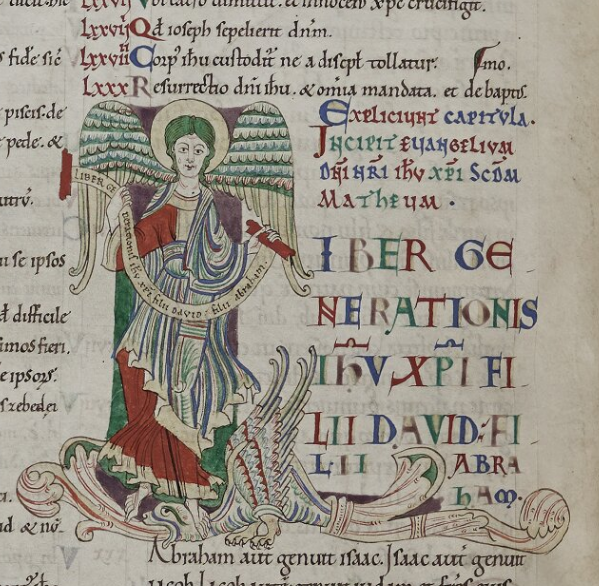

Interesting color treatments from the St. Calais Bible

The angel of St. Matthew and the dragon appear to be more of an illustration than an

illumination, even thought they form the "L" from "Liber Generationis"--the 'begats' of

the Bible. We still see the influences of Saxon work, but the details of the clothing

are becoming more Norman in look.

|

|

An example of a rare illumination from the St. Calais Bible

Presumably this type of illumination is rare. That beast-head looks like a direct descendant of the chancel arch at Kilpeck.

|

|

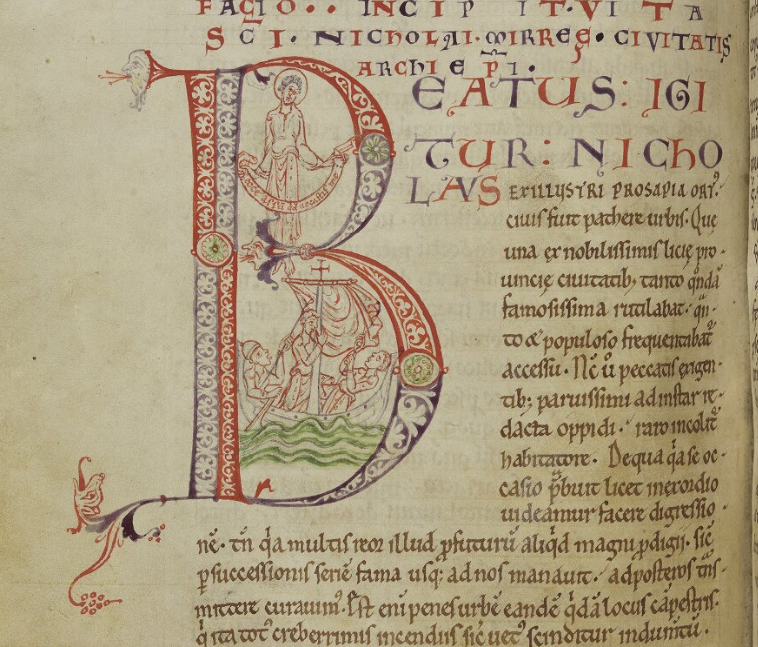

Illumination of St. Nicholas rescuing sailors

This comes from an unidentified manuscript that dates from between the 11th and 12th

centuries. It is a simple three-color ink drawing that uses arabesques and no knotwork.

Essentially, by the end of the 11th century, much of the Celtic influence in illumination

has disappeared. Occasionally, it will pop up again, but it is much more subtle-a single

knot here or there instead of an entire run of interlinked knots or zoomorphs.

As best as can be discerned, the colors are red, blue, and purple.

|

|

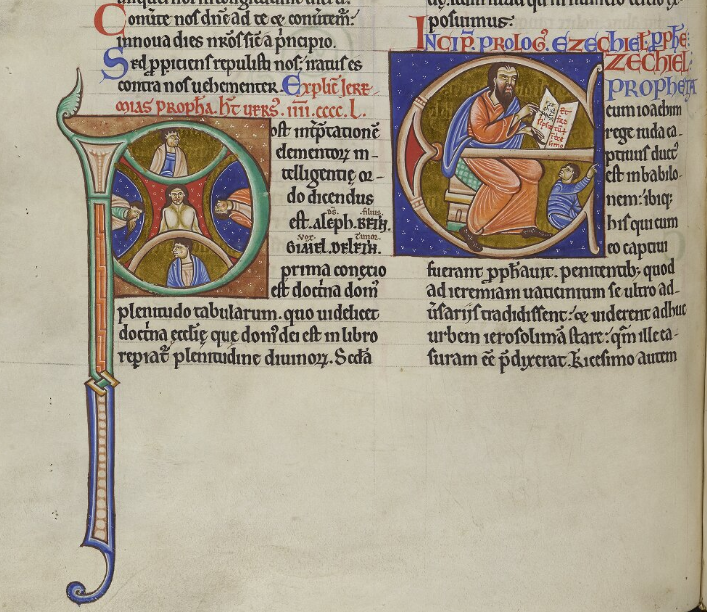

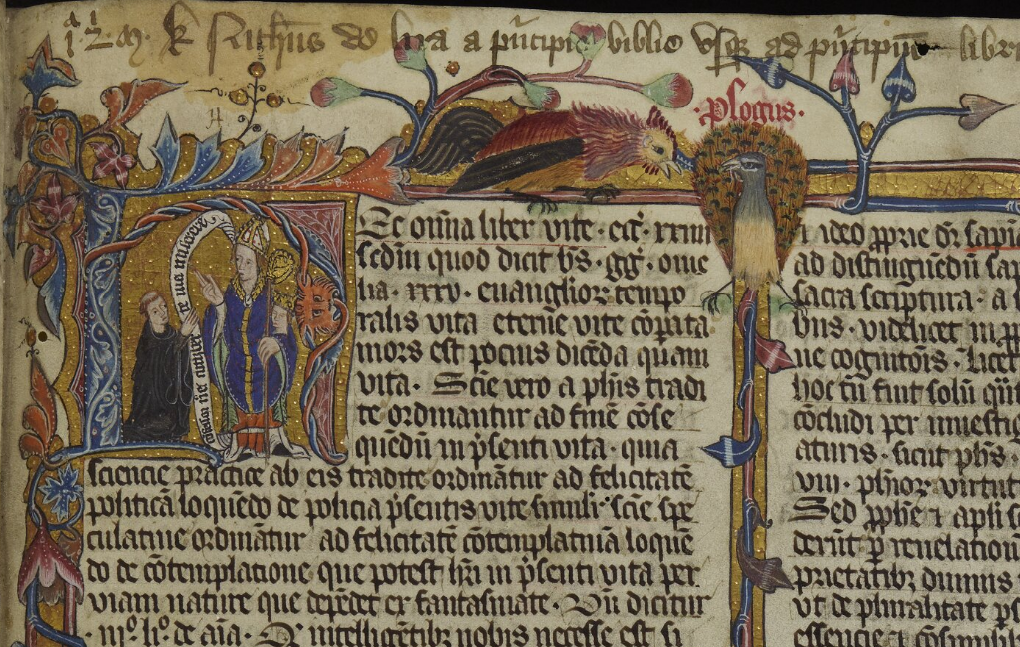

lIluminations of a "P" and an "E" from the Le Puiset Bible

The Le Puiset Bible dates to the 12th century. It was the Bible of Bishop Hugh du

Puiset, who was made Bishop at the insistence of his aunt--Matilda. Matilda would have

been the first Queen of England upon Henry I's death, however her cousin Stephen

usurped the throne, thus creating a time of anarchy. Du Puiset is best remembered as

"a noble builder, whose architects were better artists than engineers." Evidently

they did not believe in foundations and only sank the pillars of the Galilee Chapel

2 feet into the ground! This particular illumination shows a definite shift to the

Norman artistic style. There is still a bit of Saxon influence in the treatment of

the clothing. Notice that the details of facial features are becoming more

realistic--shading is used. No knotwork, nor arabesques.

|

|

Illumination of the letter "P" from the Le Puiset Bible

This illumination may show one of the last gasps of Celtic influence--a single knot.

|

|

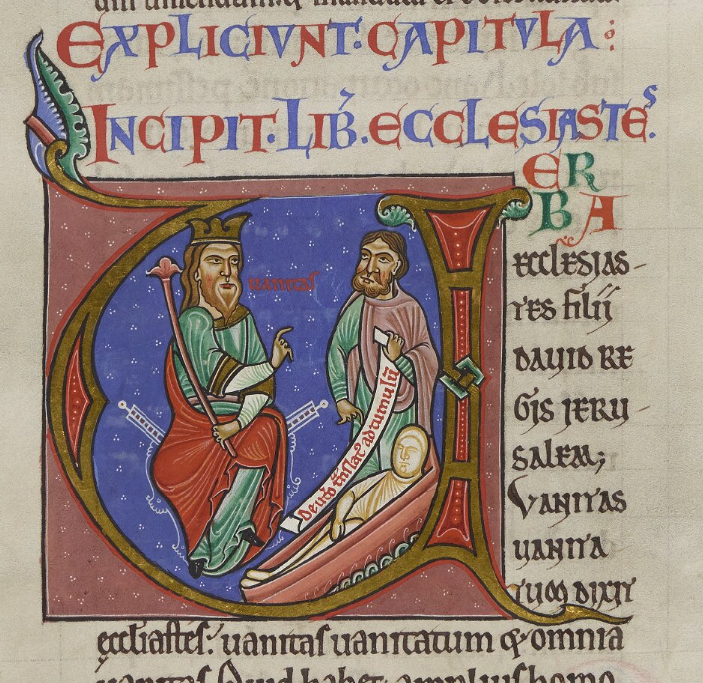

Illumination of the letter "U" from Ecclesiastes in the Le Puiset Bible

This is a depiction of King David. It is a relatively simple illumination. Saxon features on people are virtually gone and we have

subtle shading and skin tones as illuminations progress towards more realistic features.

|

|

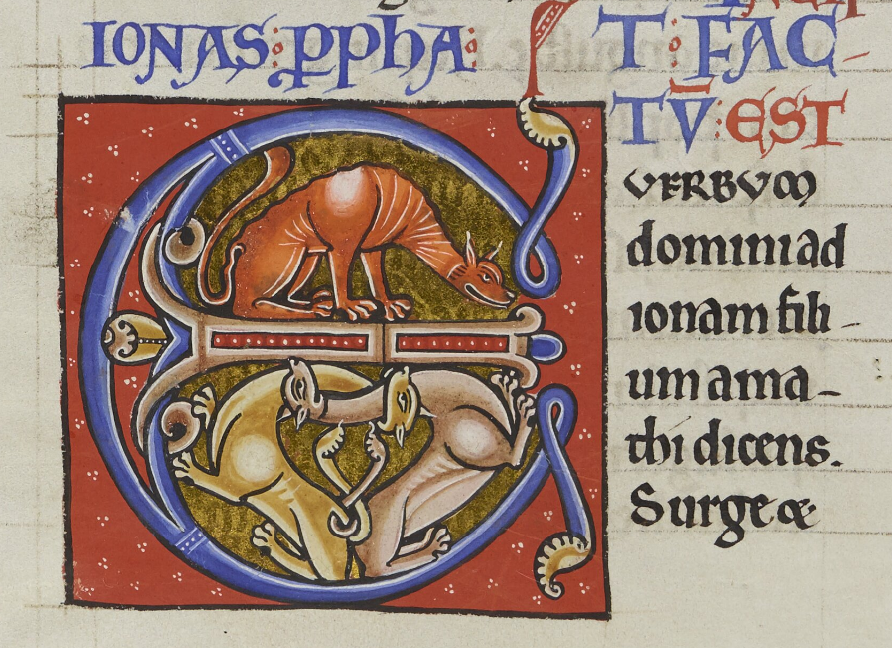

Illuminated letter "E" from the Du Puiset Bible

Fox and hounds. The intertwined tails of the hounds may be the last of the Celtic

knotwork we see. There is still some of the stylized Celtic influence here, but the

animals are beginning to be detailed with a bit more realism. This is a relative term,

of course...

|

|

Illuminated "E" from Maccabees in the Du Puiset Bible

This is obviously a battle scene. Note how similar it is to the Bayeux Tapestry in terms of armor.

|

|

An illuminated "E" from the 13th century

We are now well into the Gothic period. This is a depiction of a bell- or

carillon-player. The new artistic style we see is diapering or quilting. With the

Gothic period, we begin to see an artistic shift to more decoration in both illuminations

and architecture. One is given to wonder why a carillon player is using claw hammers.

|

|

An Illumination from a 14th century manuscript

This is a depiction of St. Cuthbert. Whenever a saint is depicted, he or she is

typically shown holding the instrument of their martyrdom or an object that is closely

linked to their sainthood. In the instance of Cuthbert, the object is the head of Owswald.

Note how naturistic the borders have become and how much more decorated the lettering has

become. The later Gothic period is best known for it's highly decorated art and

architecture.

|

|

An illumination of a wedding

Note the interesting treatment of the border around this illumination and the

diapering of its background. Much to our amusement, the wedding party appears to be

cross-eyed.

|

No image available online

|

Once we move into the Renaissance period, illumination shifts towards realism and more

secular topics. Even in the thirteenth century, literary or scholarly works (as opposed

to ecclesiastic works) were illuminated. Typical examples would be found in bestiaries.

These should probably be considered illustrations rather than illuminations, though the

techniques were essentially the same.

WOODWORKSTEAMPUNKRAILROADSLIBRARY

WOODWORKSTEAMPUNKRAILROADSLIBRARY