WOODWORKSTEAMPUNKRAILROADSLIBRARY

WOODWORKSTEAMPUNKRAILROADSLIBRARY

by Magister Eldred Ælfwald,

© 2025 Eldred Ælfwald / J. T. Thorpe

You only get recipes by attending class.

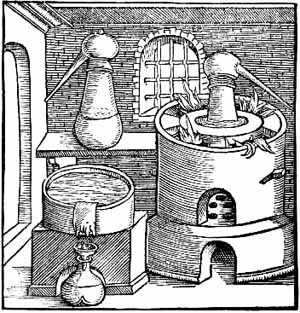

Cordials (also called liquers) date back to the thirteenth century. Arnold de Vila Nova, a Catalan alchemist, wrote The Boke of Wine during this time and

described the distillation of wine into aqua vitae and the flavoring of these spirits with herbs and spices. Some books refer to this as aqua ardens

or brandewjin (literally, burnt wine)--referring to when the distillation process produced enough alcohol that it would burn. These spirits were thought to

have restorative powers, but it was not until the eighteenth century that cordials began widespread use as drinks for pleasure instead of alchemical and medical potions.

During the Middle Ages, alchemists and monks distilled or infused in alcohol every sort of spice, fruit, flower, and leaf in attempts to discover cures for disease,

create the Philosophers Stone, etc. The manufacture of these liqueurs were closely guarded secrets, and even today, the process of creating the digestif known as

Chartreuse (c.1605) is known only to a small handful of monks in France.

Cordials (also called liquers) date back to the thirteenth century. Arnold de Vila Nova, a Catalan alchemist, wrote The Boke of Wine during this time and

described the distillation of wine into aqua vitae and the flavoring of these spirits with herbs and spices. Some books refer to this as aqua ardens

or brandewjin (literally, burnt wine)--referring to when the distillation process produced enough alcohol that it would burn. These spirits were thought to

have restorative powers, but it was not until the eighteenth century that cordials began widespread use as drinks for pleasure instead of alchemical and medical potions.

During the Middle Ages, alchemists and monks distilled or infused in alcohol every sort of spice, fruit, flower, and leaf in attempts to discover cures for disease,

create the Philosophers Stone, etc. The manufacture of these liqueurs were closely guarded secrets, and even today, the process of creating the digestif known as

Chartreuse (c.1605) is known only to a small handful of monks in France.

Towards the middle of the sixteenth century (and arguably as early as the mid-fourteenth century), production of cordials became less the province of alchemists and monasteries when distilleries began producing commercial quantities of the liqueurs. In 1575, the Dutch distillery of Bols began producing an anisette liqueur, and Der Lachs (Germany) began producing Danzig Goldwasser in 1598. To all appearances, the medicinal virtues of cordials were forgotten during the 1700s.

A slightly out-of-period liqueur recipe from Sir Hugh Plat's Delights for Ladies(c. 1609):

A slightly out-of-period liqueur recipe from Sir Hugh Plat's Delights for Ladies(c. 1609):

How to Make True Spirit of WineSide note: the book also contains a gingerbread recipe

Take the finest paper you can get or else some Virgin parchment: straine it very tight and stiffe ouer the glasse body, wherein you put your Sack, Malmesie, or Muskadine; oyle the paper or Virgin parchment with a pensill, moistened in the oyle of Ben, and distill it in Baleneo (water bath or bain marie, used to heat liquids gently during distillation) with a gentle fire, and by this meanes you shall purchase only the true spirit of Wine. You shall not haue aboue two or three ounces at the most of a gallon of Wine, which ascendeth in the forme of a cloud, without any dew or veines in the helme; lute all the jointes well in this distillation. The Spirit will vanish in the ayre, if the glasse stand open.Spirit of Spices

Distill with a gentle heat either in Balneo, or ashes, the strong and sweete water, wherewith you haue drawne oyle of cloues, mace, Iuniper, Rosemary, &c. after it hath stood one moneth close stopt, and so you shall purchase a most delicate Spirit of each of the said aromaticall bodies.

From Renfrow's glossary:

Sack: a strong, light colored wine from Spain, c.1600

Malmesie/Malmsey: a strong, flavorful sweet, white wine

Muscadine: muscatel, a sweet rich wine made from Muscat grapes

The word 'liqueur' is derived from the Latin liquefacere which means 'to melt, or dissolve'. this refers to the methods of flavoring the brandy or whisky (from the Gaelic uisage beatha), which forms the base of the liqueur. There are several methods of obtaining the flavor from the fruits and spices. They are maceration, distillation, and percolation. The final result of any of these methods, however, is that the flavor of the spice or fruit is dissolved into the alcoholic base. The choice of method used depends on the source from which the flavor is being extracted and on the particular flavor desired from the flavoring agent. Some flavoring agents will yield different flavors, depending on the type of extraction used.Although Shapiro provides a very conscise definition of the three methods, Blue provides us with some missing details.

Maceration is the simplest process. The most delicate of the fruits and spices (i.e., strawberries, raspberries, peaches, bananas, or aromatics) are soaked in high-proof alcohol for anywhere from weeks to several months--depending on how long is required to release the flavor into the alcohol. This process is generally used when the heat of the distillation process would burn and alter the taste of the fruits/spices.

An alternate form of maceration is infusion or, somtimes digestion. Dry ingredients are moistened until soft and then covered with heated spirits. Just like making tea, the spirit gradually takes on the flavor of the "tea".

Percolation is similar to the traditional method of brewing a pot of coffee (before the advent of the automatic drip coffee makers and freeze-dried crystals). The spirits are heated, pumped up to the top of the vessel, and sprayed over the ingredients at the top. As it drips back down into the main part of the vessel, the alcohol is infused with the flavor. The process is repeated until the desired flavor has been achieved. Vanilla beans and cocoa pods are processed using this method.

Distillation is generally the preferred method of professional cordial and liqueur manufacturers--but as it requires a license to perform, it is illegal for the average home-brewer to perform. Howver, the process is intended to extract and concentrate the aromatic elements instead of producing alcohol. The desired flavoring agent, which has already been mascerated, is heated and allowed to condense in a coil that extracts the concentrated flavors. This is often repeated many times with large amounts of the flavoring agent and reduced to a relatively small amount of liquid. This produces a very strong essence to be added to the bulk of the alcohol base.

Returning to Shapiro's wisdom:

It should be fairly obvious from the above descriptions of the methods used, that some would be more suitable than others for extracting the flavor from a particular source. A juicy fruit could easily undergo masceration, providing a juice that could be added to the base. It should be noted at this juncture, however, that citrus liqueurs which were common (oranges having worked their way from the Orient to Spain by the ninth century), were not made from the citrus juice, but from the oils and flavorings extracted from the rind of the fruit, generally through percoloation. Distillation or percolation are quite suited to extracting flavors from harder and drier sources, such as many spices, or from the skins of certain fruits.Even when using the same general method, different flavors can still be extracted from the same flavoring agent. With distillation or percolation as the method of extraction, a very different flavor will be produced if the base liquied is water than will be acheived if an alcoholic base is used. In many spices, a much more bitter and astringent flavor will ensue from the use of an alcoholic base as opposed to one of water. Depending on tastes and the type of liqueur desired this may, or may not be desirable and the choice of a base liquid should, therefore be carefully considered.

Once an aromatized base has been prepared by one of the above methods, or by a combnination of these methods (if several aromatic/flavor sources are used, different methods for the extraction of these essences may well be a necessity) the remaining steps in the production of the finished liqueur are set forth in Hannum's book Brandies and Liqueurs of the World as follows:

- The mixing of the final blend of aromatized bases and, if necessary, aging.

- The mixing of the aromatized base with the desired alcohol and any desired sugar and/or water.

- A generally short period of aging to rest the final product and to allow the marrying of the aromatics to the alcohol.

- Colorization.

- Cold stabilizing.

- Bottling.

Most of the recipes we have ready access to specify sugar as the sweetening agents for cordials and liqueurs. In ancient times, dates or figs were used. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance, honey was readily accessible and was the sweetener of choice. Although cane sugar was known in Europe, thanks to the Moors who conquered Spain, it was not until the sixteenth century and substantial importation of New World sugar that became plentiful enough to be used in lieu of honey.

In most of my recipes, I prefer to use honey as a sweetener. Honey presents two challenges to the cordial-maker. First, it will substantially color the cordial. This is not a problem in and of itself, but it does affect the clarity of the final product. More importantly, honey has a very large impact on taste. Honey has flavor beyond simple sweetness--the flowers visited by the bees impart their own aromatic qualities. Pick a honey that complements or enhances the flavors of the fruits and spices of the cordial. Subjectively, honey is also two or three times as sweet as sugar, and is already in liquid form. The ratio of honey to alcohol will be different than a simple sugar syrup.

In order to be considered a cordial, the minimum sugar content of a liqueur is 20% (200g suger/liter) up to 35%. Most neutral spirits that are used as a base for homemade cordials are approximately 70 to 80 proof. A 1:1 or event 1.5:1 ratio of alcohol to sweetener brings the flavor and sugar content into the right range. If you use honey, that ratio jumps to a minimum of 2:1 alcohol to sweetener. A high-proof alcohol will literally require watering down and then sweetending to achieve the correct flavor and proportions.

5 different alcohol bases (white brandy, vodka, apple vodka, gin, Everclear) were used for the maceration. The sweetening agents (honey, sugar syrup) were added in the correct proportions after a month of masceration. The goal is to show the qualitative differences between the combination of alcohol and sweetening agents. An example of incorrect proportioning was intentionally provided as an object lesson.

A word of caution: To my best knowledge, distillation of spirits without a license is illegal in the United States. This means the "traditional" method of creating a cordial is not legal, and I will not discuss it here. As a substitute, a "neutral spirit" such as vodka, gin (used in present day England), or white brandy can be used. If pure alcohol (190 proof) is used, it should be diluted with water to decrease its potency and put it in the correct alcohol content range for a cordial.

In general, the modern method for creating a cordial is to start with a "neutral spirit" and then flavoring it by steeping fruits, herbs, spices, various syrups and/or extracts for varying time periods which are typically one month in duration. Many modern recipes for cordials and liqueurs recommend the use of various extracts for flavoring. Although using a neutral alcohol as a base for a cordial is an acceptable alternative to the legalities surrounding distillation, it is strongly recommended that the remainder of the cordial recipe adhere to more traditional methods and ingredients (for full marks in a competition).

For best resultsm a white brandy is favored by cordial connoisseurs, as it is produced from grape wine as period recipes suggest. Any "white" whiskey or vodka will do. I have heard from fellow cordial-makers that the cheaper brands of alcohol have made them ill (due to a higher level of impurities), but that may be an allergic reaction to the base ingredient of the alcohol being used.

In general, here are the supplies I used to prepare and bottle cordials

Follow the recipe, making adjustments to your own taste or experimentation. When your infusion time has lapsed (usually 1 month), strain out what ever you used to flavor your cordial in order to eliminate potential sources of later contamination. Once your cordial is relatively clear, put it in a clean jar or bottle. Seal it and let sit undisturbed for a day or two to allow any particulates to settle out. Decant the cordial into a clean bottle (preferrably a nice looking one) and seal it.

If you used fruit for your flavoring, you may consider reserving the residue you initially filtered out for an adult ice cream topping as some of my friends have suggested.

Renfrow, Cindy. A Sip Through Time: A Collection of Old Brewing Recipes 1994.

Shapiro, Marc. The Meadery

Compleate Anachronist 60: Alcoholic Drinks of the Middle Ages.

Jagendorf, M.A. Folk Wines, Cordials, & Brandies New York: The Vanguard Press, Inc. 1963.

Crosby, Nancy, and Sue Kenny. Kitchen Cordials. Wesport, MA: Crosby & Baker Books. 1994.

Wilson, C. Anne. Food and Drink in Great Britain: From the Stone Age to the 19th Century. Chicago, IL: Academy Chicago Publishers. 1991. ISBN: 0-89733-364-0.

Blue, Anthony Dias. The Complete Book of Spirits. New York: HarperCollins Publishers, Inc. 2004. ISBN: 0-066-054216-7.

|

Ealdercote and the images contained therein are © 1997-2025 J.T.Thorpe and C.M.Grewcock

Last updated December 2025 |